Whenever I listen to interviews with authors, I’m always interested to know their writing routines. I think this is of interest to both established and aspiring writers. When you start off with the aim of getting 80,000 to 100,000 words from your brain onto the page, the obvious question is ‘How shall I do it?’

Closely related to this are the questions ‘How many words can I write a day?’ and ‘How long does it take to write a book?’

The writer of commercial fiction is often contracted to publish a book a year. This means he or she may be writing the first draft of one book, while editing another book, and publicising yet another! You may wish to be a commercial genre writer, or you may wish to be more like James Joyce, who spent years on a book (and reportedly could spend a whole day on one sentence). Or Donna Tart, who has written few books, with long gaps in between, but has consistently been critically and commercially successful. What kind of a writer do you want to be?

The first full-length novel I wrote (and it’s one of those novels which will stay in a draw for now) was an historical novel of 140,000 words. It was too long, but I did get a manuscript request from an agent, which suggests it wasn’t awful. During the process of writing this book I learned how best to get words on the page, and what kinds of routine suits me.

During this time, my wife was working shifts at a local hospital, which meant sometimes she would have to start work at 7am. I got into the habit of getting up early with her, and using that time in the morning to write until I had to go to my own job for 9am. I found that I was never more productive than at this time in the morning. Even on days when I had a large block of time in, say, the afternoon, I seemed to lack the flow and clarity I found first thing in the morning.

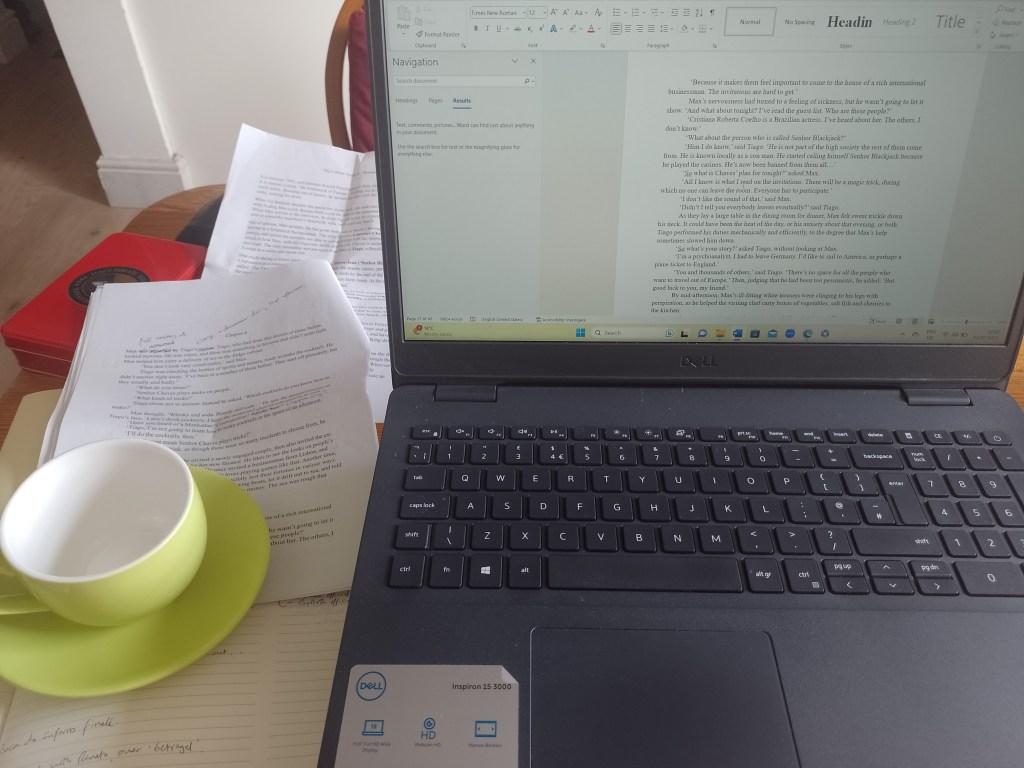

Thus, my writing routine was set. For some reason, I use a particular lime green cup and saucer on writing mornings, filled with strong black coffee. I wouldn’t call it superstition, but rather there’s something about the ritual of a routine that I’d prefer not to change if it works.

As I learned to rewrite and redraft, I found that this detailed work was best saved for later in the day. Early morning was where I found the creative spark, but not necessarily when I had the keen eye for detail needed for editing.

Famously, Anthony Trollope would write in the mornings before he went to his job at the Post Office. He would write 250 words each 15 minutes. Writing between the hours of 5:30am and 8:30am, that put him at around 3000 words per day. I heard an interview with Linwood Barclay, who during the writing of a recent novel found getting an Uber into town gave him a surprisingly productive time and place for writing. So during the writing of that book, he kept getting Uber rides into town.

I think another reason writers want to know about other writers’ routines is that we are insecure and want to compare ourselves. We ask ourselves the question, ‘Are others writing more than I am?’, or ‘Do other people find it as hard as I do?’ This suggests that no matter how experienced or professional a writer is, there is always a part of them that doesn’t know what they are doing. Creative processes are mysterious. It’s not like changing a bike tyre, or altering your boiler pressure, with step-by-step videos available on youtube.

Whatever you find works, whether it’s early in the morning or late at night, the key is consistency. If you are sporadic, or can’t find a routine, that word count will stay low. If you can get into a habit, even if you write a little at a time, you will be surprised at how the word count goes up and reaches your target.